The logical jump from Identifying Emotional Payoffs in the game you’re preparing for (or playing) would be to go straight to: Well, how do I make those emotions happen in the right order and proportion to satisfy all the people involved?

But if you went straight there, you’d be jumping the gun. There’s a couple more Key concepts and theoretical underpinnings to dig into before we start getting all practical about it.

This post is going to be about what most people would call the spectrum of Agency vs Railroading. Which is a great framework that is plenty for most GMs, especially new ones. But when we start talking about Horror, it requires a more granular look at what makes it up. Because much of what makes Horror horrifying, as folks called out in the comments of last post, is the sense of loss of control. (And as a bonus, realizing the deeper components of Agency vs Railroad is going to help you craft a more satisfying game in any genre!)

Some questions to consider for yourself before I start spouting off Wordy Bastard opinions and such:

-

*WTF is Agency, really?

-

Is “Railroading” truly the opposite of that?

-

Given that I’m presenting Agency vs Railroading as a spectrum, how far into each spectrum are you comfortable with?

-

How far in either direction is “too extreme to be fun anymore” for you?*

Thought through ‘em? Good. So here’s the thing about the Forest of Agency vs Railroading… it’s made of Trees. And it can be hard to see the individual Trees because our brains are fundamentally Lazy Beasts.

But when you zoom in really close, you discover that it’s mainly just two types of Trees in this particular Forest. And each can be considered—needs to be considered—as their own separate spectrum if you want to make full use of this concept.

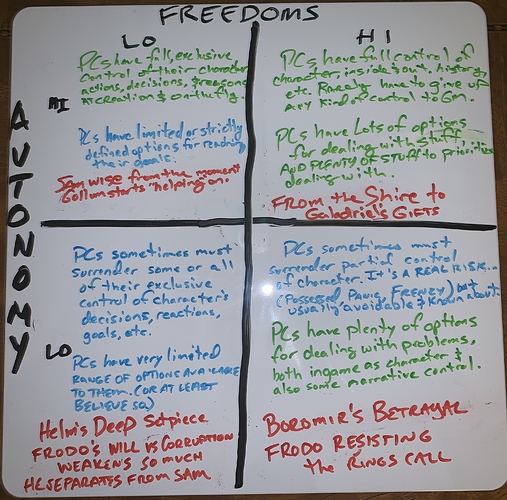

The two spectrums that make up Agency/Railroading are Autonomy and Freedoms. And each of those types of Tree can be broken down even further.

So, by Autonomy, I mean specifically: the degree to which the player has control over their character, and whether any portion of that control is shared with the GM (or occasionally, other players).

I’m talking about everything— from interior landscape stuff like backstory, emotions felt, goals, preferences, intentions, decisions, opinions, and reasons why—to external stuff like visceral reactions, obvious actions and how they go about them (e.g. slowly because tired, or slowly because meticulous, or slowly because it’s something they’ve never done before), how much they divide their attention and alertness to the other parts of their surroundings as they do so.

By Freedoms, I mean specifically: the range of options available to both the character and the player to choose from in trying to reach their goals or deal with their current situation.

Like Autonomy, this can be divided tidily up into two broad classes of option—Situational freedoms define what approaches and actions are available to the character within the narrative reality of the story at any given moment (There’s an Eye Beast: Attack it? How? Hide from it? Where? Run? What direction?)—and Story freedoms are about the degree of narrative control the Player has to elaborate on setting details and “world facts” like in the Spotlight Method discussed in ICRPG Vigilante City (it’s a city street, so it’s bound to have some parked cars and stoplights, right?). In more narrative abstract game systems like FATE this control can extend quite a bit further than setting.

Okay, so with that framework in place, I’m going to close this post with a grid and a quick observation about it. I used LOTR as example because more people are likely to be familiar with it than any horror flick I could pick.

Notice: LOTR is a gigantic epic, but if you look at it in chunks of story, it goes Top Right, Bottom Right, gradually Top Left creeps in, then Bottom Left AND THEN back to the Shire in Top Right Land, all flush with new heroic skills and traits and no one is in any significant danger of losing control of their character’s actions.

As with ALL gaming—but especially so with Horror Gaming, which quite often RELIES ON some kind of loss of control as the source of threat/fear (even if just as trapping)—if you start in one quadrant and stay there the whole session (or campaign) your game will likely feel stagnant, like you’re somehow leaving some money on the table and can’t figure out why.

For a horror game to feel like a Horror Game, the GM needs to have an idea how and to what degree the risk of losing Autonomy and available Freedoms will change over the course of the game. The better that trajectory matches the emotional genre arc your players are looking for = the more satisfied everyone will be with your Horror Game.

I’ll throw an example of using this in a Horror Genre in the comments. Because damn. I am a Wordy Bastard.