Hey gang,

After re-reading Hank’s post about what he calls the Challenge Curve, I decided to expand on that idea and tackle another issue: Energy.

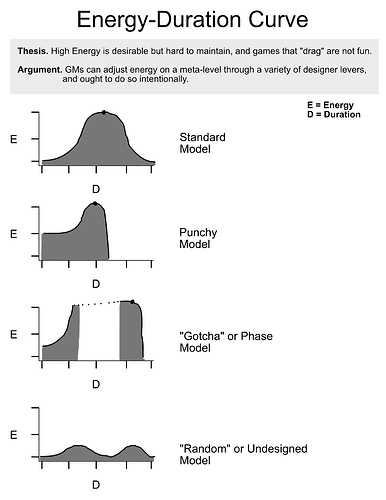

Most GMs strive to host games that are fun, high-energy, and exciting. In this sphere, we talk about things like the 3Ds, 3Ts, DEW, LOG, monster AI/tactics dice, and so on. These often exist on a mechanical level and serve to adjust what I’m calling and Energy-Duration Curve.

Energy is excitement, the stakes, and the costs of failure.

Duration is the length, in real time, of a scene. Let’s say a full duration scene is about an hour.

As much as we’d like for all of our scenes to be bangers, that high energy play is hard to maintain. It’s hard both as a player and GM, and both mechanically and narratively. If every encounter you design is a life or death fight with a D4 timer as the only thing between you and utter failure, it’s like a horror movie with an extended scene of extreme, viceral body horror and loud music. We get desensitized, and those scenes quickly lose their potency. On the other hand, lengthy scenes that are boring are also … boring. We need contrast.

My argument is that we can, and ought to, consciously and intentionally play with the common types of energy-duration curves. Let’s take a look at them.

In the Standard Model, a scene starts with low energy. The GM describes the scene, players interact with it, and then after a few minutes something exciting happens; monsters attack, a trap is triggered, or an NPC reveals a secret. Energy increases not only because of mechanical interactivity (fun gameplay), but also because the players care about what’s happening. This energy climaxes and then slowly declines thereafter.

These scenes are the bread and butter of most experienced GMs. It has a natural narrative structure, and there is a generous period of high energy - it’s not very taxing on the GM or players. The players have time to make some tactical decisions and deploy their abilities. Players who like “playing the game” usually enjoy these scenes. The downside of that, of course, is that there is a relatively short period of high energy. Most of the time is build up or afterglow - and it’s a lengthy scene.

In the Punchy Model, the scene starts out with good energy. The players are thrown right into the thick of things, it quickly escalates into a maximum energy climax, and then ends shortly thereafter. There’s tons of damage being exchanged, timers are short and perilous, and the players have a lot of buy in. These scenes usually have the players “burning” their big spenders (high level spell slots, valuable consumable resources like potions, using a narrative token) to help make sure things end in their favor. The stakes must be high - both mechanically and narratively. These can be some of the most fun scenes, and are usually taxing on the GM if they’re fully committed to running it with appropriate haste. The main drawback to these scenes is that you can’t deploy them often, these are the jump scares. To maintain potency, you have to use them sparingly or you risk over-exposure and exhausting the table. Also, there may not be enough time for mechanically-inclined players to make a plan, execute the plan with their abilities, and adjust their tactics in response to outcomes.

In the “Gotcha” or Phase Model, we start out with a Punchy Model, and then after an interlude, reveal that the scene isn’t over; subvert expectations. The second-phase of the boss fight starts, the skeletons are reanimated, the NPC ally acts out their betrayal while the party is vulnerable, and so on. In very short order, the scene ends. These are basically extended Punchy scenes, but we can get away with extending them because of the interlude. These are low energy moments that allow us and the players to rest. If done properly, this “rest” is sustained by interest and mystery.

The last model here is the “Random” or Undesigned Model. These are usually what we see when GMs don’t put any real thought into how the scene may unfold. Notice that the scene duration is long, and although there are moments of higher energy, they are short lived and never spike to an actual climax. These are the 20x20 ft. rooms with 2d12 orcs that walk forward and hit or miss with no mechanics, and the town shopping scenes. In the orc fight, random critical hits represent the peaks. In the town shopping scene, the peaks are chuckle-inducing jokes or a haggling attempt. These are also poorly executed random encounters - “Oh look, bandits attack. Roll for initiative.”

I would argue that this last model is the last desirable. If the players are uninterested, the mechanics are bland, or there aren’t any real stakes, these scenes are wastes of time. They should be short and not overstay their welcome. Note, however, that this model does not account for scenes where the players are interested in the scene – even if it’s technically “low energy”. If the players are socializing or roleplaying around a campaign (perhaps revealing a character secret, goal, or something), these are actually closer to the Standard or Punchy models, just with lower peaks. These are natural interludes and clever GMs let them unfold naturally.

Expansion of these models, and combining them together, is how GMs might go about organizing full sessions, story arcs, and campaigns.

What do you guys think about these models? What other ones can you think of and which do you use most?

(the high-energy, long-duration story arc ending boss fight is one that I didn’t include here)

AC